Description

The following text is a shortened and supplemented version of SPROUT D4.9: Impact Assessment and City-Specific Policy Response: Budapest Pilot

In Budapest, a strategic goal is to develop modal shift opportunities between public transport and shared mobility services. To this end, in recent years, BKK has developed a system for setting up mobility access points based on international examples (for example: London (Kilraine, 2021), Tel Aviv, Paris (Connexion France, 2019), etc.). The purpose of designing these sites is to make shared mobility services reliably available in a concentrated area.

For defining the location of mobility hubs, a pilot process was simulated relating to the shared micromobility vehicles that can be parked solely at (micro) Mobility Points. The Budapest Mobility Plan defines the city structure of Budapest as divided into five zones, depending on mobility needs. This differentiation has an impact on the development of Mobility Points. As there are greater mobility needs in the city centre, the aim of this use case was to create a denser network of Mobility Points within a maximum 1-2-minute walk in this area. In the transition zone, this would increase to a 4-5-minute walk. These stations can be used with privately owned vehicles, too.

Based on the service level, three three types of Mobility Points can be distinguished:

- (Micro) Mobility Point: in densely populated areas, at every 150 metres for micromobility vehicles only (bicycle, scooter, cargo bicycle)

- Mobility Point: in a densely populated area next to micromobility vehicles, dedicated carsharing and shared scooter parking at every 250-300 metres

- Mobility Station: at larger intermodal/transport hubs, a more extensive Mobility Point for shared modes of transport along with additional services (for example: delivery pick-up point, luggage storage, etc.).

Within the SPROUT project, BKK planned to establish a network of mobility points. In the city centre, mobility points should be accessible within a maximum of a 1- to 2-minutes walk; in a broader transition zone, this would increase to a 4 to 5-minute walk. Those distances are in line with a user survey carried out in Paris, which indicated that the highest share of potential users considers a 2 minutes’ walk (90%) respectively a 5 minutes’ walk (43%) acceptable to find an e-scooter (6-t 2020, 19).

There are different kinds of mobility points, following a hierarchy: the smallest solution is micro-mobility points for scooters, bicycles, and cargo bikes at every 150 meters; mobility points also include car sharing offers at ca. every 250 to 300 meters; and finally, mobility stations are located at larger intermodal transport hubs, which can also have additional features such as pick-up points, or luggage storage.

The intensity of use and the potential need to adapt the number and size of parking spaces to user behaviour are monitored using vehicle data (for shared vehicles) and regular site visits (for private bicycles and scooters).

Properly implemented, micro-mobility parking zones can also contribute to a safer design of junctions, for example through better visual relationships when car parking spaces are converted.

To understand the effects of implementation of the mobility points, the Budapest team analysed the impacts based on simulation through the Unified Transport Model of Budapest, which is a strategic transport model with all mobility modes. To make the model more reliable a new assignment procedure (point-to-point) for micromobility users was added to procedure sets. More information about this analysis is available in ANNEX 1 of SPROUT Deliverable D4.9.

The cost of the implementation of a single Mobility Point is 1,500 Euro. Therefore, the total cost of the implementation of all the Mobility Points in District 6 is approximately 130,000 Euro. Because it was not possible to run a real-life test, the operational feasibility and financial sustainability of the pilot measurement could not be measured. As a result, the assessments are based on simulations and assumptions. Based on the results of the modelling, there will be 1,600 hours/day travel-time gain in the network according to the optimistic scenario, 1,110 hours/day according to the average scenario and 580 hours/day even according to the pessimistic scenario.

A potential source of revenues are fees for private mobility providers. According to the surveys and the workshop, however, the overall operational costs of the shared mobility providers that used to operate free-floating systems are likely to decrease.

The formulation of policy responses follows a Stakeholder-Based Impact Scoring (SIS) approach. The following paragraphs outline the results and findings from applying this method to the Padua pilot case.

Practical information on the SIS approach is provided under the section Analysis Phase and Policy Responses

One of the main barriers for the implementation of the Mobility Point Network in Budapest is the multilevel municipality system: the City of Budapest needs to cooperate with the local districts, and each district has its own demand. Besides that, the new-type micromobility vehicles (e-scooters) are not defined in the National Road Code. Because of this lack of legislation, it is difficult to regulate public space use by shared mobility services and their vehicles. Additionally, there is no regulation to collect and monitor shared mobility user data.

To address this problem, stakeholders suggested to establish a city-wide regulation for dealing with micromobility and public place reorganisation targeted at road operators and shared mobility service providers. This could take the form of a capital decree in the future.

Based on the assessment and the problem identification, the following addition to the pilot project was derived:

Shared micromobility points with regulation that requires public space designers to plan space to store shared micromobility vehicles within a specified zone, and that will define the number of dedicated spaces for shared micromobility devices.

For subsequent stages, the pilot project in combination with the proposed policy solutions will be referred to as alternative pilot.

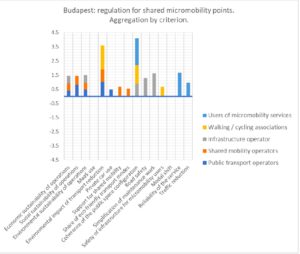

The relevant stakeholders that participated in the selection and assessment of policy response and their stated criteria (aspects they find particularly important) are listed below:

| Public transport operator |

Economic sustainability of operations Social sustainability of operations Environmental sustainability of operations Increase in MaaS use Decrease of the environmental impact of transport Decrease in private car use |

| Mobility operators |

Increased support for shared mobility Economic sustainability of operations Social sustainability of operations Environmental sustainability of operations Decrease of the environmental impact of transport Increased share of eco-friendly transport modes |

| Infrastructure department |

Economic sustainability of operations Environmental sustainability of operations Coherence of the public space configuration Increase in road safety Simplification of maintenance work |

| Walking or cycling associations |

Coherence of the public space configuration Increase in safe infrastructure for micromobility users Increase in modal shift Decrease of the environmental impact of transport |

| Users of micromobility services |

Reliability of the service Decrease in traffic Coherence of the public space configuration |

Practical information on the selection of stakeholders can be found in the section “Co-creating and utilizing scenarios” and in the SPROUT catalogue of urban mobility stakeholders

The next step in a SIS evaluation is the attribution of weights by the stakeholders to their criteria. This shows the relative importance that the stakeholders attach to each criterion. To evaluate this, a survey was set up to be distributed to all stakeholders within each of the pilot cities.

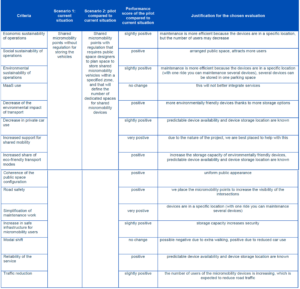

While the pilot project without additional policy action is taken as a baseline, the alternative pilot that also involves the obligation for public space designers provide space for storing shared micromobility vehicles within a specified zone (alternative scenario).

Compared to the pilot as it is, the impact scoring showed that adaptation of binding standards for micromobility points has positive effects for all stakeholders. Following the analysis, coherence of the configuration of public space and the reduction of the environmental impact of transport are the most important advantages. The advantages are especially pertinent for the infrastructure operator and the users of micromobility services, yet no stakeholders are expected to be negatively impacted by the implementation of the regulations.

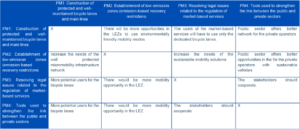

Building on the previous steps and the policy solutions that went into the alternative scenario, SPROUT partners derived a list of policies, based on the SPROUT policy inventory. The policy response consist of a set that combines an infrastructure measure, a regulation, a legal clarification, and the strengthening of exchange between the private and public sector. This mirrors the double role of cities as facilitator and as regulator. The following policy measures have been suggested:

- PM1: Construction of protected and well-maintained bicycle lanes and main lines

- PM2: Establishment of low-emission zones (emission-based recovery restrictions

- PM3: Resolving legal issues related to the regulation of market-based services

- PM4: Tools used to strengthen the link between the public and private sectors

The suggested policy measures were then assessed through stakeholders, using the Recommended Indicators for Assessing Policy Implementation Feasibility and User Acceptance of New Mobility Solutions

All policy measures were found to be mutually supportive:

The feasibility assessment revealed concerns of stakeholders regarding the financing of bike infrastructure and about potential lost revenues for districts, inter alia from the collection of parking fees. In order to reduce the financial costs of micromobility hubs, a ‘less is more’ design policy was suggested.

Core of the policy response is to define collaboration agreements between the municipality, the administrative departments and the city districts on the implementation of sustainable mobility measures. The agreement could have the form of a capital decree and include city-wide and binding planning specifications, that oblige urban planners to provide space for all modes of mobility; and provisions for the the re-organisation of public space targeted at road authorities and owners of the space.

Key learning and recommendations

The following key messages were derived from the pilot:

- Create cooperation between the public transport and the shared mobility modes.

- Regarding the design of the Mobility Points, “less is more” because of the financial and operational requirements.

- Combine data and simulation techniques for finding the best locations before installing the micromobility points and demonstrating the impacts on mitigating the negative externalities of transport (air pollution, traffic congestion).

SPROUT materials and tools

Data requirements

Policy responses were derived based on results from the impact assessment and financial feasibility analysis combined with the Stakeholder-based Impact Scoring methodology.

Further information

SPROUT D7.2 Policy paper contains a section on micro-mobility hubs which builds upon experiences from Budapest.